Introduction

The recollections are in my mother’s own words and were written down by me during conversations over several weeks. The only “editing” I did was verbal - for example, keeping her on the subject in question, as she reminisced, to avoid too many digressions into other areas. As she spoke about each subject I would occasionally interrupt to ask “How?”, “Why?”, “What next”, or “Why did that happen?”. I have not paraphrased anything or used my own words - she was very particular in making sure I wrote down exactly what she said. In typing it up I merely punctuated it and set it out for ease of reading.

Tony Evans, Middlesex, July 1998.

Home

I was born at 93 Heathcote Road, Miles Green but by the time I'd left home to go into service we had lived at five different houses. When I was about three we moved to a rented part of Sam Titterton's farmhouse in Miles Green. Two years later we moved back, this time to 91 Heathcote Road. After five years there we went to live at 226 High Street, Halmer End, and then two years later moved into the Miners' Reading Room in the High Street as caretakers. Finally, just over a year later, we exchanged with the couple who lived in a cottage opposite at 73 High Street. I don't really know why we made all these moves, we certainly didn't have to. I suppose it was just for reasons of domestic convenience.

I had four brothers and sisters. First was Tom. He was born at High Lane, Alsagers Bank on 25th August 1902. He was killed in the Minnie Explosion in 1918. Then came Annie, born on 10th October, 1903, also at High Lane. Then there was me, and then Marion, who was born on 2nd March, 1909, while we living at Titterton's farm. Last was Harvey, born on 12th September, 1912, at 91 Heathcote Road, Miles Green.

My father was 29 when I was born. He was a stonemason when he was a young man but when I was born he was working at Podmore Hall Colliery. He suffered badly with asthma and had a job at the bottom of the pit shaft searching the men for matches etc, when they came down for their shift. When the last man was down he was able to come up to the pit-head. He later worked at the Minnie and he was there when he died in 1931. Apart from his lay preaching he didn't have any other job. I only remember him being out of work once and that was for a short time after the Minnie explosion.

My mother was the same age as dad when I was born. She was a primary school teacher at Silverdale. I don’t think my mother’s family were very much different than their contemporaries. After all, her father was a miner and her brother George (my uncle) went to work in the pit in Wales. Her mother, Grandma Higginson, was ambitious, though, for her children. She always wanted the best for them. She was a very reserved woman and didn’t mix much. They were a decent, hard-working, staunchly Methodist, clean-living family. When (mother) married, and again after the children were a little older, she did supplementary teaching - I suppose it's called supply teaching now. She did this at schools at Red Street, at Chesterton and at Halmer End. She carried on doing it until she retired at 60. After this she got a job as the cashier at Audley cinema! She loved it and did every night. In fact she was still working at the cinema when she died aged 76 in 1953. When she was teaching she worked the regular school hours, from 8 to 4 pm I suppose, but when she worked at the cinema she worked from 5.30 to 10.30 pm every evening from Monday to Saturday. She never worked when we were children. Except for Harvey we had all left school when she went back to work as a supplementary teacher.

I’ve no idea where my mother and father met. When I got older I always thought that they were an ill-matched pair. She was a quiet, inoffensive, gentle woman, whereas dad was authoritative, very articulate and had a strong personality, although he could do no wrong as far as Grandma Higginson was concerned; she thought the world of him.

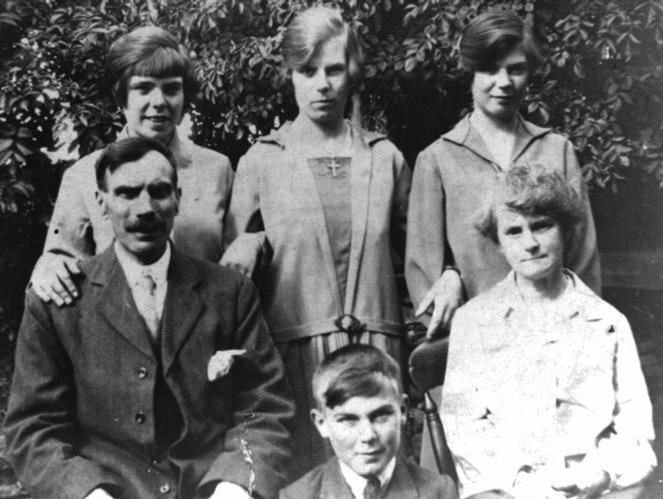

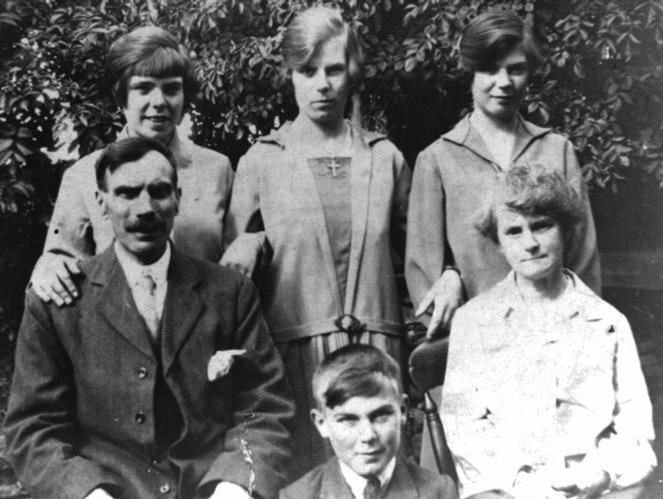

The Challinor Family, circa 1928

Back (l to r): Gertrude, Annie, Marion. Front: Robert Henry, Harvey, Gertrude Selina.

I can remember my maternal grandparents, John and Florence Higginson. He was a miner and they also kept a small general store in Silverdale; the kind of place where you could get anything from a packet of pins to a basket of groceries. I have only one small but vivid memory of grandmother and that was when I was about 4 and my mother took me once to meet her when she arrived at Halmer End Station - I can just remember seeing this little old lady, dressed in black, walking towards us along the platform. Grandad lived to be 91 and when grandma died he went to live with his eldest daughter, Jenny, who worked all her life at Emburey's Bakery.

I don't remember my father's father at all but I do remember Grandma Annie Challinor. She lived with my dad's sister in Fenton and I remember her when we used to visit, which wasn't all that often. She was a nice, comfortable, little old lady, again always in black with a little bonnet and cape. She was about 74 when she died.

The domestic routine

I can't really remember the house where I was born, I was only about three when we left. Of course, it's still there and doesn't seem to have changed much.

I can remember the farmhouse. I suppose I was about four when I used to help Mrs Titterton in the "butter making pantry" which was a large alcove set off from the large kitchen which was always spotlessly clean. I remember helping with the churning and watching the cream separate from the milk, as well as sitting watching the ducks and chasing the chickens in the farmyard and helping to feed the pigs. The farmhouse is still there and looks very much as it did all those years ago.

I can remember 91 Heathcote Road quite well. There was the usual "entry" between the two houses and you walked straight off the pavement through the front door and into the parlour. There was a horse-hair sofa and armchair in the parlour, linoleum on the floor and a large rug. We had two big black china vases on the mantelpiece together with two, matching, black rearing horses which I suppose were made out of cast iron. The usual mirror was over the fireplace and we had one or two pictures. We also had a small harmonium which dad used to play. Of course the parlour was only used for special occasions. From the parlour you went through a door into the kitchen which was a nice warm and cosy room where the family lived on a day to day basis. We had the usual black leaded kitchen range, a table and chairs, a small settee against the wall and a Singer sewing machine which was worked by a treadle. Through the kitchen you went into the scullery, that was the back kitchen. This had a stone floor, a brick built boiler with a coal fire underneath it for the weekly washing and a large, shallow brownstone sink with one tap. Through the outside door into the back yard and there was the coal-house and next to that the double wooden-seated lavatory which was emptied once every few weeks by the "night soil men".

To go upstairs the staircase went from the middle kitchen and at the top you turned left or right into the front or back bedroom. There were two small bedrooms at the back, which only had a bed and a chair each and a curtain across the wall to provide a place for hanging clothes. The front room had our iron bedstead, with valance, a wash-stand with bowl and soap dish and a dressing table. And, of course, we had chamber pots under all the beds. Although our homes were all rented the furniture was ours and we took it with us wherever we moved. Most of it finished up years later at my brother Harvey's house in Halmer End. Looking back, the homes were always dark and gloomy although we thought nothing of it at the time. The only light was by oil lamp and that was only downstairs; upstairs in the bedrooms it was always candles. The first time we had bright lighting was when we moved into the Reading Room, which was gas lit.

Monday was washing day and it was a full, hard day's work. First the boiler in the scullery would be lit and the washing divided into separate piles. Some hot water would then be taken from the boiler and put in the tin bath; the boiler would then be topped up. We then started the washing. The whites were first and when they were done they would be transferred to the dolly tub; the coloureds would then be put in the bath. The whites would be agitated with the dolly peg and then put in the boiler. While they were boiling we would wash the coloureds. Then they would be put aside to go in the boiler. Then we did the towels. Each pile was put in the boiler in turn and then put aside to be rinsed. The last things to be washed would be the "delf" (I've no idea why it was called this) - these were the dirty pit clothes. When all this was done the boiler fire would be let out and when the water had cooled a bit some of it was kept for cleaning up and the rest poured away down the drain in the backyard. The dolly tub and tin bath were also emptied. The dolly tub was then put underneath the mangle and re-filled with cold water for rinsing. The whites were again done first and after being agitated with the dolly peg they were put through the wringer. All the other piles were then rinsed separately and put through the wringer. We then had to make up starch for the table linen and most of the coloureds (aprons etc). If you couldn't dry the washing outside it was put over the rope rack in the kitchen. No wonder it was a day's work. And there was still the dusters and the stockings to do; my mother always left these for me to do when I got in from school.

Most women started the washing about 8 o'clock, when the children had gone to school and by the time they had finished and cleaned up the tubs and the mangle and swilled the yard, it would be 4 o'clock or later. If you didn't do your washing on Monday you were thrown out for the rest of the week because it was ironing on Tuesday, then turning out the various rooms (parlour or bedrooms) on Wednesday, and Thursday and Friday was spent doing the kitchen - blackleading and cleaning the grate and ovens etc. The ironing itself was a day's work for a family - the irons had to be heated in front of the fire; I remember my father made a frame that fitted onto the bars of the grate and this held our two irons which were used alternately.

All our clothes were mended by mum and us girls although mum wasn't very good at needlework; in fact, she wasn't too domesticated at all. Annie, my eldest sister, was a very good needlewoman even as a young girl and she made quite a few clothes. We bought our clothes as and when we could afford them and usually from the Co-op in Silverdale. I suppose we must have passed some clothes down to each other and we had quite a few given to us from time to time by our better off cousins. Shoes were bought at the Co-op and we never had any hand-me-downs. When I was about ten I can remember wearing clogs. I had a very nice pair of lace-up boots which I loved and when the soles wore through we had them made into clogs. My dad used to mend all the family's shoes. He never helped out with any of the domestic chores and as for painting and decorating and other repairs, the landlord always arranged that.

My father did a lot for us as children. He always put us to bed and nursed us. We always went to dad when we were sick or troubled, never to mother. He was always very attentive. He read to us regularly but I can't remember anything in particular. He used to teach us numbers and counting using an abacus and we used to sing hymns either separately or all together. We rarely went out as a family, except when we went to chapel on Sunday or to chapel functions during the week. When I went out with him it was usually for a walk around the lanes and often through Brook Fields and up Peggy's Bank.

We all helped out in the home and the jobs changed as you got older. When we lived in Miles Green, the regular Friday chore when we got in from school was to clean the front step with a whitening brick, we called it step-stone, which was rubbed on the step and dried white. When you'd done that you had to swill the entry by throwing buckets of water down it and brushing it out into the road. We always knew whose turn it was to swill the entry. By the time we moved to Halmer End (to 226 High Street) I was about ten or eleven and we were all helping regularly with the housework. One chore I didn't like was when dad was mending shoes and I had to stand by him and hand him the nails - I think he called them Bradleys. Many's the time I've stood there for over an hour holding those nails. In 1919 we moved to the Miners’ Reading Room. It was my job, when I wasn't at school, to take his snapping to him at the pit. Although it was more than a year since the explosion they were still bringing bodies out and I can remember clearly two occasions when my dad said that if I went down at a particular time I would see them bringing bodies out and I can remember being in his office when they were brought out. While we were caretakers at the Reading Room we were responsible for the cleaning and maintenance of the Billiards Room, the Games Room and the Reading Room itself. My sister Annie and I were always up early to clean these rooms before we went off to school. By the time we left the Reading Room and moved across to the cottage I had left school and Annie, who was then about 18, had left home to go into service. My mother had gone back to teaching, leaving me in charge of the home. I was 14. This carried on until my younger sister, Marion, left school and I went into service.

Bedtimes were quite strict; as children we were always in bed by 7 pm. It relaxed a bit as we got older but we always had to be home by 10 o'clock if we ever went out anywhere. No exceptions were made for holidays.

When we were little dad always put us to bed, mum never did. We always shared a bed - my sisters and I slept in one bed and Harvey had his own bed in his own little room. This was how it was all the time I was at home. Mum and dad of course slept in their own bed in the front bedroom.

Friday night was always bath night for the children. The tin bath, which was kept hanging up in the back kitchen, was put in front of the range on the hearth and we all took it turns to have a bath - usually in the same water! As the water cooled more hot water would be added; the last one to bath always complained because by then the water was nearly cold. In the mornings we all washed in the stone sink in the back kitchen; we used household soap, I think it was something called "Minerva". I don't remember any of us having a toothbrush.

The Miners’ Reading Room, Halmer End

The Reading Room was two miners’ houses knocked into one. Going up Halmer End on the right hand side was the Wesleyan chapel and next to it were two houses which the chapel owned. Then there was an alleyway which led into the fields at the back and then came another row of miners’ houses. The first was occupied by Mr & Mrs Fred Jones, who used their front room as a little sweet shop. The next two houses were the ones which were knocked into one to be the Reading Room. After this row came what we called the Railing Row - because the pavement rose up above the level of the road and there was a high wall and railings. All this, and the Reading Room, was knocked down when they built the council houses and flats in its place.

At the Reading Room both the downstairs front rooms were turned into one large billiards room. There was a full size billiards table, a rack for the cues at one end and at the other there was always a huge fire which was burning from 9 o’clock in the morning, through the day, until closing time at 10 o’clock. Of course, the pit provided all the coal. Around the fireplace there were wooden forms under the window, and various chairs. There was a scoreboard on the wall and the chalk hung down from the ceiling on a piece of string. The fireplace at the other end was never used. The original red tiles on the floor were left around each fireplace and there were red quarry tiles underneath the billiard table, which was set on the wooden floor. Remember that this was two houses knocked into one, so there were two back kitchens: one of these we called the Domino Room, where the men played dominoes and draughts. There was a fire in there as well, in the black lead grate. There were two long trestle tables and forms each side, where the men sat and played. The kitchen at the back was hardly used, it just had the sink and the cold water tap.

Upstairs was where the magazines were, in the front bedroom. This was the Reading Room itself. Again there was a trestle table and forms - I don’t recall any chairs. I don’t remember the fire ever being used - I can remember my father having a moan sometimes when the men brought magazines and papers downstairs to read because it was warmer. Every day the paper was delivered, always the “Daily Herald”. There was the “Weekly Sentinel” and one or two monthly magazines: the “Strand” was one and one I remember because I thought it was so uninteresting was the “Exchange and Mart”. There were other illustrated magazines which I don’t recall. The back bedroom wasn’t used. The other home, of course, was our own accommodation. We had the kitchen, scullery and all the upstairs, just as a normal home.

The Reading Room was open from 9am until 10 at night, six days a week, and it was closed on Sundays. It was very well patronized because I remember teams visited for billiard handicaps. They came from Loggerheads, Talke, Butt Lane, all around. When they came we were busy with tea and currant buns and sandwiches. We had soft drinks - lemonade, lime juice and sarsaparilla, and in winter cups of Bovril. These visits were mostly on Saturdays and they were considered to be quite an event. Apart from the matches, the Reading Room was well attended, especially in the evenings, although we had elderly, retired miners from the village who came and sat there for hours during the day. I remember Bill Kirkham, an old miner who lived just above the reading room - he was there every morning at 9 o’clock to be the first to read the “Herald”. Another old member was an old chap named Lingard - I think it was Frank Lingard senior - who lived in a cottage opposite the Reading Room. The men had to pay to be a member. It was a small yearly subscription, but I can’t remember how much it was. If there wasn’t a billiards match on we probably had about 20-25 men in each evening, more so in the winter. During the day it wasn’t so busy, just one or two elderly, retired miners would come in for a chat. When we left and moved across to number 73 it was still flourishing, but I can’t remember if it was still open when I left home to go nursing in 1931.

Meals

Meals were always taken in the kitchen. As children we all sat down at the table together for any meal. Mum did all the cooking when we were little but by the time I was 13 I was helping with it and then did it all myself when she went back teaching.

Cooking was done in the kitchen on the range which had a small oven on each side. Kettles for boiling water and saucepans for cooking were put on the hobs which were on each side of the fire. There was always a kettle of water boiling on the hob.

Breakfast was usually about 7.30 in the morning, except for dad who had gone to work by them, and we all sat down a the table for it. We nearly always had a small bowl of porridge and a round of toast - no marmalade or anything - and tea. On Sunday we had a small rasher of bacon with either a tomato or an egg. When we were little we used to share an egg between two of us.

When we were at school we took sandwiches, either cheese, jam or apple. We were usually all at home for tea which was bread, margarine and jam.

At weekends we had a stew on Saturday (we called it lobby) and a milk pudding at mid-day and then a bread and butter tea. Sometimes we had a jelly or a tin of fruit. On Sunday we had rabbit and vegetables for dinner with apple tart and custard. Tea was the same as on Saturday.

Mother wasn't a particularly good cook and apart from Sunday's apple tart she did very little baking. Vegetables were always bought fresh - usually from the Co-op - together with fresh fruit, mostly apples and oranges although we did have the occasional banana. We usually had a tin of fruit on the shopping list every week.

When we lived at the Reading Room we kept some poultry. We had about 50 chickens, including Wyandots, Leghorns, Buff Orpingtons and Rhode Island Reds. The Leghorns were the best layers. My father looked after them and I can remember doing the feed. We boiled all the vegetable peelings and mixed this with "meal" which we got from the Co-op to make a mash. This was then put into small troughs in the "scratching pens". We had two of these. In the morning we also scattered a mix of wheat, corn and oats among the straw so that the chickens would have to scratch for it. The warm mash was given every evening.

We only ever had meat at weekends - and it was usually rabbit from Newcastle market, 1/6d for a good one! We never had tinned meat. We all had an equal share. When we were at the table talking was not encouraged and I can't remember food ever being left uneaten. As long as we sat properly at the table that was all that was required. We had to stay at the table until father gave us permission to get down; we wouldn't have dreamed of getting up and leaving beforehand. The only formality we really had was at the weekend when dad always served the dinner.

Parents and discipline

Mother was very easy going but never showed a lot of affection. I don't ever remember sharing anything with her - never remember telling her if I was fed up or anything like that. She never seemed to be really interested much in what we were doing; I think she was wrapped up in her own activities. My father was the one you could talk to about anything and as I have said before he was the one we went to if we were sick or worried about anything.

We were very respectful of our parents and I can't remember any of us giving them any backchat. We were very close to them, especially dad, and didn't have any other adult confidants. We were never allowed to join in discussions as children. whether they were talking to each other or with other grown-ups, we had to sit and listen. We were strictly brought up and were always conscious of the need for good manners and polite behaviour - my father particularly stressed the need always to consider other people's points of view and feelings.

The only discipline I can remember was the threat of it. There was always a stick hanging up by the range in the kitchen and although it was threatened many times I don't ever remember it being used. I honestly can't remember that we were told off about anything much - we seemed to know instinctively what we could or couldn't do or say, and also what we should do. The only punishment I ever remember was to be sent upstairs where you remained until you were allowed to come down again but that didn't happen very often. My father was by far the dominant influence on our behaviour and usually one look from him, he could look very severe if he wanted to, was enough to keep us in order.

We were a very close family and we all got on well and were close friends. It's strange but I have no memory of my eldest brother Tommy. If anything I was closest to Marion, my younger sister, we were very much alike. We must have had squabbles as children but I can't remember any at all.

Family activities

On our birthdays we always had little friends to tea - there was nothing spectacular but we always remembered birthdays. Bearing in mind that this was a period of much depression and hardship I don't ever remember having presents at all and there was certainly no attempt to have any special food - the birthday just came and went without too much fuss.

The only musical instrument we had in the house was the harmonium and dad was the only one who could play it - and that was always hymns! We all sang in our own way but my mother was a good contralto - before she was married she belonged to a local choral society. We all sang in the Chapel choir, except for Harvey. We didn't sing together regularly in the family - it was only very occasionally that we had a sing-song round the harmonium. Dad was a good baritone. One memory I do have is that on Sundays, when he used to carve the rabbit, he always used to say to mum "Come on Kit" and then they would start singing together "Hail! Smiling Morn! That tips the corn with gold; At whose bright presence darkness flies away, flies away!". They would sing this together as they served the dinner, it was always great fun!

I can't remember there being any games in the house, board games and the like - and my father wouldn't have a pack of cards in the house! I remember years later, when my sister Annie was married and had her own place, she always had to hide the pack of cards when mother called round to see her! At Christmas we usually had visitors calling in and we sometimes played games then - blind man's buff, musical chairs and the like.

My father was a very well read man and we had quite a collection of books - most of them on politics or philosophy. He used to read to us. My favourite book which I read myself was "Grimm's Fairy Tales" and we usually had books given to us as prizes for good attendance at Sunday school every year. Annie had one I remember, I think it was called "A Peep Behind the Scenes", which was about a little girl called Rosalind and her life with a circus. I often used to take it to bed with me and Annie used to grumble at me for that. There was a good library which we belonged to at the Sunday school. My dad always read the "Daily News" and then the "Daily Herald" when that started. Mum used to have a monthly teaching magazine called "Teachers World" and dad also had the "Strand" magazine. And, of course, we always had the "Evening" and "Weekly Sentinel".

The first funeral I can remember, but it wasn't in the family, was when I was about six and it was the funeral of a little girl called Alice Jervis who had died of diphtheria - she was only four. I remember going with three or four other little girls, I can't remember who took us, to see her laid out in the parlour at her house in Miles Green. She was laid out in the coffin under the front window and her mother was sitting on a chair by the foot of her coffin. The thing that sticks in my mind is the little red rose that her mother had laid across her chest. One thing I've thought about many times over the years is that she was laid out like she was for people to see and yet she died of diphtheria which was extremely contagious.

In the family, of course, I remember Tommy's funeral vividly. It was 18 months before his body was recovered from the Minnie pit and I would have been nearly 13. When he was brought out we were living at the Reading Room and they brought him in his coffin and rested it on the billiard table. The family and relatives were gathered round and we had a short service and sang the hymn "Nearer My God To Thee". He was then taken up and buried at Alsagers Bank churchyard but strangely enough I have no memory of actually going up there; but I do recall coming out of the churchyard and feeling this tremendous sense of relief that he was buried at last. We all wore mourning - the girls had little black and white check dresses with white straw hats and a black ribbon round them. Mother was all in black and dad wore a dark grey suit and his beige trilby which he always wore for best. We wore those dresses for the whole year, after which we had deep mauve dresses - mother wore the same - and we wore those for another year, to school and everywhere. It wasn't so unusual because there were many other families in the same boat. The material was bought for us by family friends and was made up into dresses by a lady in Halmer End; she did nearly all the dressmaking for the funerals in the village.

Of course I remember father's funeral very well. That was in 1931. We were living in Miles Green then and I can remember he was laid out on a table under the front room window. I can remember one evening he was laying there and we were all sat round the kitchen table having supper when we heard a noise, a bang, from the front room. My brother Harvey went ashen, he was petrified. I was the only one who would go in to see what it was and it was the curtain, blowing in the slight breeze, had knocked an ornament off the window sill. My dad's hearse was horse-drawn, black horses. He was taken to our chapel in Halmer End for the service. There was quite a big turnout for that because dad was well known in the area and there were many of his political and preaching associates there. From there he was taken up to the churchyard at Alsagers Bank. By this time mourning was beginning to be less formal and although my mother was in black for 12 months, she didn't go into second mourning - and, apart from the day of the funeral itself, none of the rest of the family wore mourning at all.

Don't forget that after the Minnie explosion funerals were a commonplace event and it wasn't unusual for there to be four funerals in Halmer End on the same day. We knew all the families involved and as children we took great interest in comparing the various corteges and the number of wreaths. In fact, funerals became so common that I can remember my brother Harvey, as a little boy, playing funerals in the house. He and our cousin, Spencer, would take the long horse-hair cushion from the sofa and lay it across two chairs - this would be the coffin - on it they would place my dad's cap and our school hats which would be the wreaths! Harvey would stand by the chair at one end of the cushion and cousin Spencer at the other - they would be wearing their caps, which they would take off while they sang "Rock of Ages". They would then carry the cushion slowly round and into the next room while one of them would mumble the funeral prayer! My father never discouraged them playing like this because he thought it was good for them to make a game of it. I'm sure he was right.

The first wedding I remember in the family was my sister Annie's. She was married at 8 o'clock one Saturday morning in December 1928 - it was not unusual then for weddings to be that early. She and Jack (Brockley) were married at our chapel in Halmer End - there were about a dozen there, just the families. She wore a nice blue dress and a cream hat. It was a simple occasion; after the wedding both families came down to our house, the cottage at number 73, and had sandwiches and tea and then Annie and Jack went away to stay with his cousin at Liverpool for the weekend. Honeymoons were not the fashion then for families in our circumstances and more often than not newlyweds lived with relatives. Annie and Jack were very fortunate - they managed to rent a house belonging to a schoolteacher friend of my mother. They paid 10 shillings a week which we all thought was an exorbitant amount at the time! At that time weddings in the village were quiet affairs - most people were very hard up and there was little money to spend on weddings.

As a child I was often in and out of other houses in the village - people were always popping in to each other's homes - but there was never any formal socialising. The nearest it got was after chapel on Sunday when friends would sometimes come back to our house for a chat - but no food or any refreshments at all. We visited relatives frequently, sometimes as a family but more often as teenagers, when we went to visit various cousins in Scot Hay, Newcastle, Hanley and Fenton.

The only times we were ever taken out shopping was to go to the Co-op at Silverdale, usually for clothing. This was quite an event and we usually went with mum. The normal week's shopping - for food etc - was done on Saturday morning at the Halmer End Co-op, which was opposite Alsagers Bank Church.

We never had outings as a family. The only occasion that I remember we all went out regularly as a family was to Audley Wakes which was held on August Bank Holiday Saturday. This was a festival organised by the charitable clubs in the district; there were the Rechabites, which was a teetotal club, the Foresters and the Oddfellows. There would be two or three bands, always the Audley Prize Band, and a fair. We used to get to Audley for about 10 in the morning and spend the whole day watching the procession in the morning and then down to the Wakes' field at the bottom of Audley. The only times we ever went away as children was to stay with relatives. I used to go with my sister Marion to my Uncle Harry's cottage at Colton near Rugeley - just for a week. Most of our holiday time in Halmer End during the summer was spent blackberrying in Hays Wood; Marion and I would go out early in the morning with a 2lb jam jar and spend hours in the wood, coming home at about 5 or 6 o'clock.

Religion

Although Saturday was still a working day - we often had to wait for dad to come home with his wages before we could go to the Co-op - it was regarded as a little bit special because people expected to go out somewhere on Saturday evening. When the buses started running regularly in the late 1920s and early 1930s people used to go into Newcastle to look round the market on the Stones. Sundays were completely different and for us they were totally dominated by chapel. Our one and only chapel was the Primitive Methodists’ in Halmer End, which I believe is still there. The first minister I can remember was named Mr Shirtliffe - a very smart man, very gentlemanly, who wore a vary smart pair of what seemed to be gold-rimmed spectacles, but they probably weren’t. From when I was about 10 years old until I left home to go to work the Sunday routine never varied. At about 10 o'clock the children would go to the Sunday school classes in the various rooms at chapel and then at 11 o'clock those who were old enough stayed behind for the main morning service which finished at about 12.15. We then went home to dinner and after washing up and getting ready again we went back to Sunday school classes from 2 o'clock until just before 4 when we all gathered together for the closing hymn. Back home again to tea and then at 6 'clock we all returned for the normal evening service which lasted until about 7.15. About every two weeks the minister announced that for those who wished to stay there would be a prayer meeting after the service. We always stayed on! They ended about 8.30 or 9pm. This was a typical Sunday in our family so you see there was little time for anything else.

Both mother and father were established members of the chapel. Mother was in the choir and often used to help out at other chapels by singing in their choirs at anniversaries or on other occasions. Dad was a lay preacher and sometimes took the service. Sunday school outings were rare. The main event was the Sunday school treat which was held in the summer. We had a tea in the Sunday school after which we all went up to a field which belonged to the farmer, Mr Lawrence, which he let us use for the day, and we played games from about 4 o'clock until about 8. All the usual games, ring-a-roses, rounders, races, etc. One feature was that one of the teachers always brought a large box of sweets which were scattered about the field and we all had to go off and find them! When the day broke up all the children were given an orange and then we all drifted off home. It was always a lovely day.

As children we often went to the Band of Hope meetings which were held in our Sunday school, usually on a weekday evening. More often than not they were talks about the dangers of strong drink and we always had a lecture from Charlie Heywood - I suppose he would be regarded as a born again Christian today - who gave a very emotional speech about his conversion from drink! He was always very dramatic. At the end of these meetings we always signed the pledge!

Every Tuesday evening we had Christian Endeavour, which was a short service, and Wednesdays was choir practice. On Saturday there was nearly always a social gathering in the evening when we had games and light refreshments. In addition to this we were often at chapel one night a week during the autumn months practising for forthcoming concerts. My usual contribution when I was about 9 or 10 was to recite "The Wreck of the Hesperus" - I can still do it too! Annie and Marion would usually be in singing groups and Harvey would do something comical - he usually had a funny cross-talk routine with his friend Bert Johnson. Dad would sometimes do a monologue but I can't remember any one in particular. We always had a big concert on the first Monday in the New Year. It's interesting to recall that practically all the children in the village, regardless of whether their parents went to chapel or not - and of course many didn't - came to Sunday school and took part in the Sunday school activities. I suppose chapel really provided us, especially the children, with our social life.

We never had family prayers at home but as children we always had to kneel by the bed and say our prayers at bedtime. Religion meant a lot to us as children and chapel dominated our lives in a very happy and enjoyable way; we never found it oppressive and I can never ever remember not wanting to go.

Politics

Almost as big an influence on our lives as religion was politics and to my father the two were almost inseparable. He took a great interest in politics and I think he would have been regarded as quite left wing for the time. He was a strong supporter of the Labour Party and was vehemently opposed to privilege and private advantage in education and medicine. He often spoke at Labour Party meetings which more often than not were held in our Sunday school at chapel. I can also remember on many occasions going to Labour meetings at Audley cinema. They were always well attended and well organised, I never remember any rowdiness or disturbance. My father would talk to anyone about politics, he loved a good discussion; in fact most of the conversations in our house were usually to do with either chapel or politics. Even if he was in the garden at the front of the cottage he would soon have a group of men around him debating something or other. He was a very good platform speaker. His political views often ran into his preaching at chapel which caused some difficulties, the majority of chapel people thought that you shouldn't mix politics and religion but my father maintained that they were one and the same thing and there were often some uncomfortable moments at chapel after one of his sermons! Despite this he was highly regarded in the village.

I can remember one particular example of this after the Minnie explosion. The Bullhurst seam, where the bodies of some 15 or more victims, were lying was considered by the owners to be too unsafe for rescue work to continue and they wished to seal the workings. The men, and especially the families of the victims, objected strongly and a meeting was held at our chapel to discuss the matter. It was presided over by Mr Hill I think it was, who represented the mine owners. There was strong opposition to closing the seam and the meeting broke up. Because Mr Hill knew that my father had some influence with the men he sent word for him to see him at Apedale Hall. My father refused to go saying that if Mr Hill wished to see him he should come to Halmer End to see him. He did and I remember they sat together on Halmer End Bowling Green and talked for some time. After this another meeting was called which my father presided over. Mr Hill also attended. The meeting was a success and eventually it was agreed that the Bullhurst seam would remain open and the rescue work would continue.

The last of the bodies was brought out some six months later. Although he often expressed strong, and sometimes controversial, views my father was well liked and respected by managers as well as the men. After the explosion it was the Pit Manager, Mr Smith, who offered him the job as checkweighman at the pit and also suggested he move to the Miners' Reading Room as caretaker. He was also on very good terms with Mr Weaver who was the under manager. Mr Weaver was very good to us after the disaster. For some weeks afterwards we had boxes of groceries left under a tree in our back garden at the Reading Room and we were all puzzled where they came from. My father was determined to find out so he kept watch and one night he was there to see Mr Weaver's young son, Roy, leave a box in the garden.

For my mother chapel was the dominant influence. She took very little interest in politics and I can't recall her expressing any views at all. My father had a great influence on me as a child and I was perhaps the one in the family who was most interested in talking to him about things, whether it was to do with chapel, politics or life in general. I was living at home until I was 17 so we were very close and they were quite influential years for me.

Childhood leisure

Our pleasures as children were quite simple. During the summer holidays two or three of us would go off together with a bottle of water and a bun each for a walk through the meadows - sometimes we would take a sandwich and sit on Peggy's Bank and play hide and seek among the gorse bushes. We didn't have bicycles or anything like that. In the spring we would go off picking bluebells and in the autumn it was blackberrying. We had very pleasant and full holiday times. I can remember going to the cinema in Audley when I was about 11 or 12 - but only to the first house which started about 5.30 pm and came out at 7.30. We had pocket money; I can remember for years it was about tuppence because we always spent it on sweets - my favourite was a penny's worth of raspberry drops which I used to get at Parker's sweet shop in Miles Green. In the summer we looked forward to the "hokey-pokey" man coming; this was the ice-cream man with his pony and trap and two large tubs of ice cream. It was ½d for a cornet and 1d for a wafer. I've no idea why he was called the "hokey-pokey" man!

Community and class

The only time I can remember anyone coming to look after us was when Harvey, our youngest brother, was born. A neighbour, Marion Birchall, came in most days to look after us while mum was confined upstairs - like the rest of us Harvey was born at home.

Both my mother's and my father's families were close and almost without exception we knew all our uncles, aunts and cousins and they all meant a lot to us during our young lives. They all lived in or around the Potteries and we visited them frequently. Most of my parents' friends were in the village and more often than not they were associated with chapel.

There's no getting away from it, there was an awareness of different social class within the village but it made no difference to the way in which people appreciated each other. The ones we saw as being different were the professional people like the doctor, the minister and the schoolmaster, and the way in which this was emphasised was that their children usually went on to higher education which was beyond the average miner's family. Although there were those in the village who had different, and better paid, jobs at the pit, this made no difference to social relations - they were all regarded as pitmen. Apart from the exceptions I've mentioned the rest of us were clearly working class but we were always taught to treat everybody the same, with good manners and respect. I can't ever remember anyone ever being called "Sir" or "Madam" - the miners generally were respectful but not subservient. One of the most important persons in the village was Mr Hewitt, the schoolmaster, and you've got to be my age to remember him!

There were bound to be differences among the various families in the village - for example our family values and way of life would be completely different to those of a family where the husband spent a lot of his time, and his money, in the pub or club. Obviously there were rough families, and children, but everybody seemed to knit together amicably. The roughest families were well known, and some were notorious, but there was never any disharmony or any atmosphere of trouble. As children we had many friends who came from families who were much better off than we were - these included children of the schoolmaster, the minister and others who had senior positions at the pit. Although my sister, Marion, and I were particularly conscious of our circumstances financially we were never excluded from any of their social activities, birthdays etc., and we were never made to feel uncomfortable or different in any way; we played happily in their houses just as they did in ours.

All our homes were rented, two of them being miners' houses owned by the Minnie. The only other landlord I can remember was Josiah Lee who owned our cottage at 73 High Street, Halmer End. He was a miner and he bought the two cottages for £99; he and his wife lived in one and we rented the other.

The only savings club we belonged to was at chapel - it was the Christmas club and I think we paid 2d a week into it. My dad paid a sub to the Rechabites club as a kind of ill health or accident insurance.

There's no doubt that my parents struggled financially. Mum didn't go back to work until Harvey was 7 years old - that would be in about 1920. By this time Annie, the eldest had left school and was in service. When dad was ill and off work, usually with his asthma, one of us would have to go to Audley on Friday to draw his sickness benefit from the Rechabites club. It was about 16 shillings. His attack would usually last for two or three days at a time, sometimes he could go weeks without an attack but in winter they were more frequent. The money he had from the Rechabites club was the only assistance I remember him getting. I remember once when he was bad he'd been given a bottle of medicine by his doctor which really helped him and he felt much better. When it was finished he asked me to go to the doctor to ask if he could have some more of the same. The doctor said he was sorry but he couldn't possibly do that as that particular medicine was not for panel patients. I suppose he must have given him the first bottle as a favour. That stuck in my mind and even then, as a young girl, I thought it was wrong that there was a good medicine available but that my father couldn't have it. But that's how it was, we just accepted it.

Talking about that reminds me of the dentist. Mr Sarson his name was and he had his practice in Stoke. He would come to Halmer End once a fortnight and he would see patients in the kitchen at the newspaper shop run by Mrs Corns at 48 High Street. I remember going twice to have teeth out, I would be about 9 or 10. You sat in a chair facing the window and after the extraction he gave you a glass of water and you used Mrs Corns' kitchen bucket as a spittoon! You had to pay for the treatment but I can't remember how much it was. Poor Mr Sarson had impaired eyesight as well! My father always poked fun, saying to us to make sure we knew which tooth it was so that he took the right one out!

School

I was 5 when I started school in Halmer End. It was a very dark, old and gloomy building and I remember we sat on long forms which were in rows with about twelve boys and girls on each form, there was a desk top in front of each and these were attached to the forms at each end by an iron frame. We had sand trays to start with and then after about a year we had slates which screeched every time you wrote on them. For about the first six months we just played with the sand trays but after that we were taught to form letters in the sand. One thing I can remember very clearly was sitting on the form and the teacher giving us each a little wire frame which was in the shape of a chair or a bed, or a wheelbarrow or cradle, on to which we used to thread little beads so that when it was finished it would be completely covered in these coloured beads. I thought they were lovely.

There were no school meals then so it was usual to take sandwiches, but I never remember taking anything to drink. There was a cup on a chain attached to a tap so I suppose we just used to drink water from that. The first teacher I had was a Miss Fullelove and I remember her very well. In the infants, if you were naughty, you were made to stand facing the wall for a short time.

While I was in the infants the new school was being built and I think it opened in 1914 which was when I went into the juniors. The new school was very nice and modern, the classrooms were very bright with plenty of room and there were radiators. We had desks for two - a proper desk with a lid - and inkwells. There was also a very nice domestic science section which was very popular. Our class used to go on Thursdays and we had three months given to cooking, followed by three months on laundry. I remember the teacher well - her name was Miss Pass - she was very young and I should think she had come straight from college, everybody liked her. In cookery we made something different each week, it could be a pie, cakes, biscuits or puddings and a day would also be spent learning how to bottle fruit. We usually took our own ingredients, but if Miss Pass supplied them she charged a few pence for whatever it was we had made. The morning session finished at mid-day and in the afternoon we were each given a separate job to do, such as cleaning the cooker or the utensils or crockery etc. The last hour was spent writing an essay on what we had done during the day. Nobody liked doing this! During the three months of laundry classes Miss Pass would tell us to bring a particular garment or item to school which we would then wash, dry and iron to take home again. One day it would be a shirt, next pillowslips, then a table cloth and so on. After the washing, ironing and cleaning up we again had to write an essay on the day's work. I used to like domestic work so I always enjoyed Thursdays. While the girls were doing all this the boys would be doing carpentry.

I don't remember the teacher ever discussing things other than the basic lessons. The only thing I can recall which was out of the ordinary was when the old headmaster, Mr Hewitt, retired. He was replaced by Mr Dale and also a Deputy Head, Mr Reeves, and they insisted that every class had one period a week devoted to music. This was something new and everybody really enjoyed it. We all loved singing, especially "Nymphs and Shepherds" and it was such a change from the usual hymns which was all the singing we had had before. It was a great change from Mr Hewitt, who was a stern man. He used the cane a lot. I often remember boys being bent over the front desks and he would give them four on the backside. The girls were hit on the hands and I can remember getting whacked a few times, usually for talking!

I don't remember any organised games while I was at school, there was no school football team or anything like that. All we had was a PE class in the playground doing small exercises and marching around.

I was good at English, spelling and reading, but hopeless at arithmetic. I remember the new headmaster brought in Algebra and none of us had any idea what he was on about! Both he and the deputy head were young, with new ideas about things, and I often think he must have wondered what he'd got into, coming to Halmer End. I was 14 when I left school - I suppose, given the chance, I would have stayed on but, of course, nobody did. I remember some girls, I can name about half a dozen, from the better-off families, went to a place in Audley for private lessons until they were old enough to go to Orme Girls' School. Apart from that most of the girls I was at school with went into service.

“Better-off” girls

(This section was added in response to a question from the editor) As for the “better-off” girls - why I say they were better off is that they didn’t have to go into service for a start. Don’t forget we had no choice. There was no alternative. We couldn’t afford to travel to Newcastle and back every day and because it took a financial load off our parents, we had to find somewhere where we lived in and had our board; if you like, someone else looked after us. It was just taken for granted that’s what we would do.

With one or two exceptions, though, the girls I’m talking about all came from mining families. I was very friendly with Edith Brearley, who was the station master’s daughter at Halmer End station - she was in the same class as me at school. We were friends with the Kesteven girls - Dinah and Jane - who were apprenticed as needlewomen at Henry White’s outfitters in Newcastle. Both Dinah and Jane died only very recently. They lived in the same house at 333 Heathcote Road, Halmer End, all the years I knew them. Another friend was Poppy Smith who’d lost her father and came to live with relatives in Miles Green. They were the Holdings - Mr Holding was the local baker. They had a largish house in Miles Green. It was also the bakery, and in the grounds in the summer they had a tennis party once a week. Poppy Smith became a nurse and was a matron at a small hospital in the south of England when she died about 40 years ago.

The ones who went to the little school in Audley - having thought about it a bit more I now recall that it was mainly to teach shorthand and typing - included Agnes Taylor, Lilian Davis, Jane Kesteven for a short while until she went to Henry White’s, and Miriam Wareham. Why I remembered about the school is because I remember my sister Annie was so taken up with these other girls going that she tried a Pitman’s shorthand correspondence course to do at home, but she couldn’t persevere with it; in any case, she had to go into service, so that was that.

Agnes Taylor’s father died in a mining accident when he was 33. Lilian Davis and her sister Gertie were motherless - they were brought up by their father and uncle in a house in Miles Green. They were a very nice, happy family. The Kesteven’s father had been killed in a pit accident and I always understood that the compensation their mother received enabled them to go to Henry White’s as apprentices. They were both very successful and worked as seamstresses from their home in Halmer End. Miriam Wareham came from a well-known Audley family. I believe her father was on the council and was either the organist or choir-master at the little chapel in Miles Green. She eventually went to Orme Girls’ School.

Another friend was Annie Glover, whose mother and father were both schoolteachers somewhere in Stoke. She was the only daughter and she went straight to Orme Girls’. Then there were the three Downing daughters who were more friends of my sister Marion than me. Their father was a miner, but in a senior position, fireman or overman or something. Lucy became a teacher at Alsagers Bank Church School; Janet was also a schoolteacher and married Tom Mainwaring, of the Mainwaring bus family; Mabel, the youngest, went into nursing and I believe finished her career at St Thomas’ Hospital in London. When she retired, I understand she worked in the florist’s department at Harrods.

These, and others like Doris Lockett and Olive Harrison, whose brother, Albert, later ran the general store in Halmer End, were all our friends and all had connections with chapel. We regarded them all as being from better-off families.

Work

After I left school I stayed at home, more-or-less running the house. My eldest sister, Annie, had left to go into service and mother had gone back to work teaching. I did all the cooking and housework until I was about 17. By this time my younger sister, Marion, had left school and it was her turn to stay at home. It was just taken for granted that I would have to go into service.

One day at chapel my mother was talking to a friend, Miss Louie Roberts, who was a trained midwife and who, at that time, was attending Mrs Sidney Myott in preparation for the birth of her fifth child. Miss Roberts was engaged to live in with the Myotts at this time. She told my mother that Mrs Myott was needing a housemaid and it might be a suitable post for me. Mum and I discussed it and a meeting was arranged for an interview with Mrs Myott. I remember this very well. Mum and I went to the Myott home, Derwent House, which was on the Brampton in Newcastle. We were let in by a maid and shown to the drawing room. I was rather awe-struck and very doubtful about my inexperience and whether I would be suitable. Mrs Myott came in and chatted and put our minds at rest by saying that she preferred untrained girls because she liked to train them herself in her own particular ways. It was an amicable meeting. I was offered the job and we both agreed to think about it. Mrs Myott did say however that she would like to visit my home, presumably to see how we lived. Of course I didn't say anything but I didn't think much of this and neither did my father when we told him. Anyway, some days later Mrs Myott arrived at our cottage at Halmer End in her chauffeur driven car and stayed for about half an hour talking to me and my father. I remember thinking at the time how lucky I was in having a job more or less offered to me like this without having to go out and search for work. The following week I left home to live in at the Myotts.

The Myotts were a well-established and well-known family in the Potteries at that time. They owned a furnishing shop in Newcastle and also the Myott pottery factory at Cobridge. Mr Myott and his wife were both on the boards of governors for the Orme Boys' and Orme Girls' Schools respectively and Mrs Myott was a local magistrate. I believe that Mr Myott had also been mayor of Newcastle at some time.

I remember arriving on my first day, being shown in by the maid and then awaiting Mrs Myott in the drawing room for my instructions. She explained my duties and the running of the house and showed me around all the rooms and, of course, the back stairs, which I was to use whenever I entered or left the house. I was also introduced to the four children - four girls between 2 and 9. After showing me my own room, which I shared with another maid, she left me in the care of the cook, Eleanor Timmis, and it was she who more-or-less showed me the ropes from then on. She was very kind and very patient, bearing in mind that this was my first experience in domestic service.

We had to wear uniform which we provided ourselves. In the morning we wore a striped cotton dress, a large white bib apron and something called a "Sister Dora" cap. At 12 noon I changed into a navy blue or black dress with a frilly white apron with collars, cuffs and cap to match and we wore this until bedtime, usually about 10.30 pm. We had one half-day off during the week and every other Sunday afternoon from just after lunch until 10 pm. My half day was Tuesday and I usually went home, catching the 3 o'clock bus from Newcastle and coming back on the 9.30 bus from Halmer End. It was known as the "Skivvies Bus" because most of those on it were maids going back to work. It was the same again on Sundays. After I'd been there a couple of months the fifth baby arrived - also a daughter - and shortly afterwards the resident nanny left. Mrs Myott asked me if I knew of anyone suitable and I mentioned my sister Annie, who at the time was working as a ward maid at the North Staffs Infirmary. And that was how Annie came to the Myotts as the new nanny.

Mrs Myott was very good in one respect. Knowing how Annie and I missed going to chapel on Sunday she suggested that on our Sunday "in" we could go to an evening service at the nearest Primitive chapel. So Annie and I used to go to the chapel at Silverdale, which wasn't the nearest but it was part of our own circuit and we knew several of the people there. Of course, we had to go straight back to the house after the service where the supper table was always waiting to be cleared. That used to niggle me. I always felt that it wouldn't have hurt them to do it themselves once in a while!

As a general rule I would be up at 6.45 in the morning and my first job was to clear the drawing room fireplace and then lay, and re-light, the fire. We usually used paper crackers, which was yesterday's newspapers folded up and twisted, together with a few sticks of wood. Then the room was dusted. Next I did the same thing in the morning room and after that I had to lay the dining room table for breakfast. By the time I'd done all this it was time to sound the first gong which was to get the family up. That was at 7.30. At 8 o'clock I banged the gong again meaning that breakfast was ready in the dining room. I remember when I first started Mrs Myott took me aside to say "Gertrude, you're only waking this family you know, you're not waking the whole of the Brampton". I must have been a bit heavy with the gong! The family helped themselves to breakfast and while they were doing that we had our own breakfast in the kitchen. After breakfast Mr Myott would then take the school-age children with him when he went off to business and the two youngest went upstairs to the nursery for the rest of the day. I then cleared the breakfast things away and swept and dusted. At 10 o'clock I went to help the housemaid make the beds and at the same time Mrs Myott would go into the kitchen to see cook to give her the menus for the day and any particular instructions. At 12 o'clock I changed into my afternoon black dress and apron and then laid the dining room table for the family lunch. Mr Myott and the elder children always came home for lunch. It was the main meal of the day because the younger children would only have nursery tea in the late afternoon. I always waited on at lunchtime. After clearing up, most afternoons would be spent cleaning silver, cutlery, cupboards, etc. Tea time was at 5 o'clock - the children had theirs in the nursery. Mr Myott was not always there for tea so Mrs Myott had a tea tray. When he did come in he always had a boiled egg and thin bread slices. After tea the older children did their homework or had music lessons. After their tea in the nursery the younger children would come downstairs for an hour with Mrs Myott before going back to the nursery and they were usually in bed by 6 pm. After tea was finished we were on call to answer any bells etc until 10 pm when Mr and Mrs Myott would have a tray of coffee and biscuits in the morning room. This was a routine day.

Of course, in addition to all this, each day had its own particular jobs to be done. Monday, as usual was laundry day. They had their own laundry room and on alternate Mondays I would be sent to help the laundress, Mrs Machin, until the ironing was finished, usually about 5 o'clock but sometimes 7. Tuesday was spent "turning out" the drawing room or the morning room alternately and Wednesday and Thursday were "bedroom days" when we would do two rooms a morning. All these jobs had to be done my mid-day. Friday was given over to general kitchen work, cleaning and tidying up. Weekends were more relaxed. On Saturday we did the dusting and all we did on Sunday was to tidy up the house generally. On Sunday morning the family always went to church. Except when I was on half-day I would be on call in the kitchen.

The Myotts had a fairly busy social life and there would be occasional dinner parties throughout the year. In the summer they would have tennis parties and, of course, the usual birthday parties for the children. All of which meant more work for the staff. I was paid 12/6d a week. This was paid monthly, by cheque, which we had to take down to the cashier at Mr Myott's furnishing store in Newcastle. Although I hated having to be in service I respected the Myotts very much; they were good, considerate employers and I don't think I could have gone to a better place. I learned a lot while I was there, particularly about household management. Mrs Myott was very well organised and the house ran very smoothly. It was a very happy home and the staff got on well with each other. Despite all this and although I enjoyed the work itself, the fact that I was a maid and was regarded as somehow socially inferior I resented very much. I was always keenly aware that it was wrong and that I was worth something better than that. For example, one thing I particularly resented was at Christmas when we were each given a new set of afternoon uniform of apron, cap and cuffs. I know that this was common practice for girls in service but I thought it was dreadful. Then again, on the other hand, on my 21st birthday, the family presented me with a wrist-watch which I much appreciated and which I kept for years, until shortly after I was married when our dog chewed it to pieces!

When my sister Annie left Myott's to get married I was very unsettled. I had been there about 3½ years and I thought a change would do me good. As it happened my life changed dramatically. I left the Myotts and got a job as a maid with the Stobart family who lived in Clayton; the house is still there. It was a much smaller house than the Myott's, just Mr and Mrs Stobart, their two daughters, two live-in maids and a daily cook. I think Mr Stobart was a businessman connected with McIlroy's in Hanley. The other live-in maid was a girl called Connie Powner from Newcastle and we became good friends. After I had been there about 12 months Connie said she was leaving to go to help out at a guest house belonging to a friend near Bournemouth. As it happened there was a similar opportunity in a guest house next door, so I jumped at the chance and Connie and I spent a very happy summer, 1931, working there. It was that summer that my father died. In the October I went back to Halmer End, decided to go into nursing and, by Christmas that year, I had left home to start my general nursing training at Birmingham.

Looking back on my life as it was then it's sometimes hard to believe that it was all so long ago. I can remember people and places very clearly and what it was like in the village when I was growing up. Of course Halmer End was never the same after the Minnie explosion and especially after the pit was finally closed down in the 1930s but, despite all the many changes over the years, the village and Alsagers Bank, Miles Green and Audley are still recognisable as the places I remember as a young girl. Even when I left and eventually married and moved down south, I always regarded it as home. Whenever I used to travel up to visit, I always felt I was back home when the train slowed down as it approached Stoke Station. I was always very homesick after a visit and I still get that feeling even though it has been over sixty years since I left. In spite of all the many hardships and deprivations, and leaving aside the dreadful consequences of the Minnie disaster, life in general was very happy. Of course nearly everyone was associated in some way with the pit so even if you didn't know them personally you knew who they were - so there was a common bond and a very strong sense of community. I suppose if you've experienced something like that you never forget it.